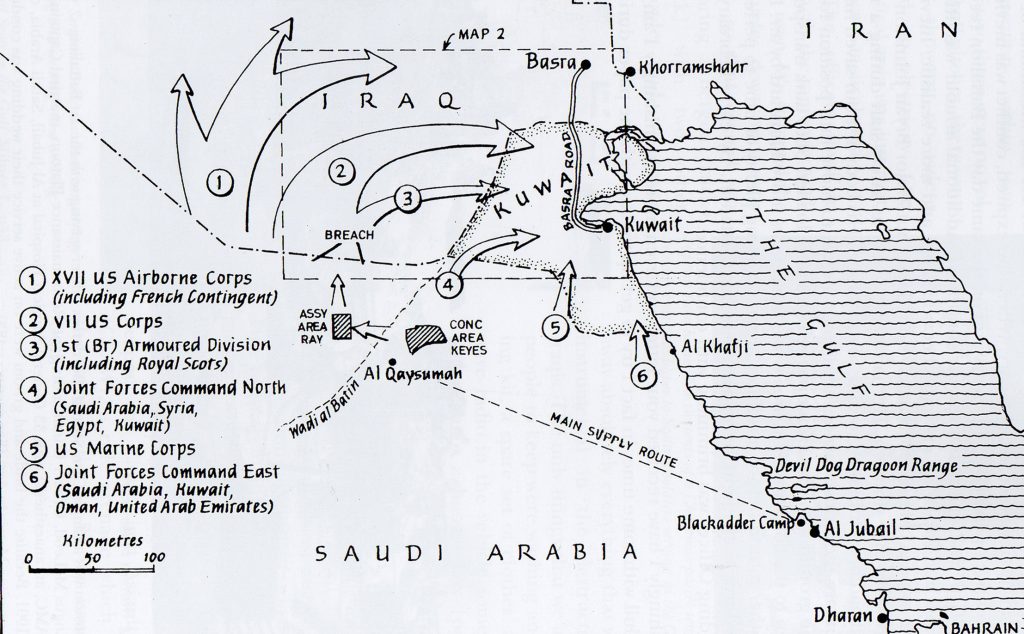

This is the then Lieutenant Colonel Iain Johnstone OBE personal report as Commanding Officer on 1 RS’s participation in Operation Desert Storm- the liberation of Kuwait from Iraq in 1991 for which it was awarded its 148th and 149th (final) Battle Honours over its 373 years of Service, Wadi Al-Batin and GULF 1991, the latter carried on the Regimental Colour..

COMMANDING 1RS BG OP GRANBY/DESERT STORM 1990-91

This is based on something written not long after the event, and I think it is important that it is relayed as it was, not as it now appears. This is an important point because, as General Rupert Smith once said, “I am becoming less certain exactly when I began to know what I know now”.

This is a personal account of commanding a Battalion during the Gulf campaign, with 4 Armoured Brigade, as part of the 1st (UK) Division. I took over The First Battalion The Royal Scots in October 1989. It was an Armoured Infantry Battalion in 6 Armoured Brigade, consisting of 3 companies each of 16 Warrior IFV, a platoon of 24 Milan ATGWs mounted on FV 432s as were a section of eight 81mm mortars, my main headquarter vehicles as well as the ambulances. There were also a Reconnaissance Platoon, a platoon of 90 electrical and mechanical engineers and a convoy of soft skinned vehicles providing support and resupply. Its strength was about 800 men. Within a week I was throwing it about as part of a battlegroup on Soltau training area. I was lucky because the next year, in 1990, our division became the Support division for BAOR, which meant that not only did we get more than our fair share of simple repetitive manual tasks, but we were also at the bottom priority for training. This meant that Soltau that year was a low-key affair with no tanks, no gunner support and an ever-increasing number of restrictions that had been placed on us to appease the civilian population. We were not at our peak.

Perhaps sensing that and not long after our return to base, Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait. We reported in at CEFT 1,1 (a combat readiness level) making us one of the few units with 95% of our established manpower and equipment in place and ready to go. As a result we thought we would be sent. We weren’t. Instead we watched suspiciously as 7 Brigade were stood by and as units were stripped to reinforce them. Eventually we were warned to be ready to chop to 4 Brigade in order to replace 7 Brigade in March 1991 on rotation. To move up to our war establishment as well as taking account of the postings that had already taken place for our imminent Arms Plot to UK we took a formed company of 3 RRF under command and moved down to Hammelburg, the Geman Infantry urban warfare training center, in our new ORBAT to shake ourselves out. We had plenty of time to get to know our new brigade headquarters or so we thought.

Our real participation in GRANBY was announced to me at Hammelburg on the 15 November….we were to load our vehicles and kit for the Gulf on 30 November.

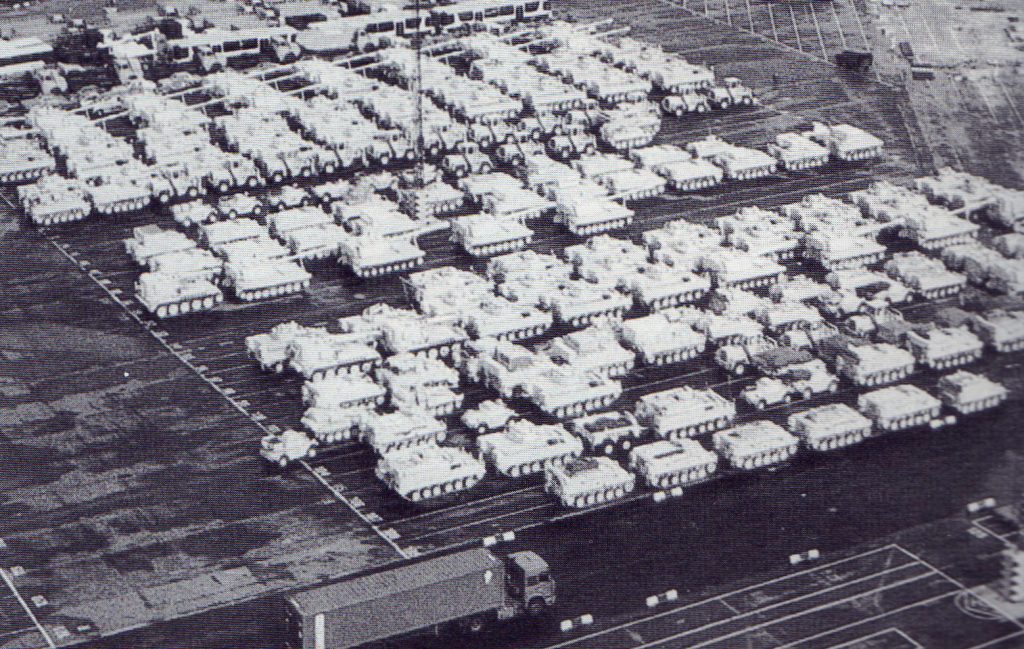

British military vehicles at Bremerhaven awaiting shipment to the Gulf

GRANBY 1.5 had been born. For us it had 5 phases:

Phase 1, Rumour Control. Phase 1 had by this time taken place. There had been a bazaar of rumour at all levels. The OPSEC was dreadful and speculation was fuelled by “experts”, both green ones and television ones. As the commander it was important to discover the truth and to stamp out rumour. This was tricky as there was a whole range of information, most of which was as well informed as mine and which certainly sounded more interesting. You see, there is a fine balance between overbriefing, underinforming and speculation, and we found it once the operation had been born by skipping the chain of command and I briefed all of the soldiers directly twice a day before battalion fitness training. Briefing the soldiers did not necessarily mean that the information got to the wives so the Families Office and the HIVE (families meeting center) had to become information nodes. Nothing unsettles people more than uncertainty. This was a lesson that permeated the whole campaign.

Phase 2 : The Preparation. At least by Phase 2 we had been told that we were actually going. The problem was that we had to be ready to ship out in a fortnight. The schedule was tight and the help that was imposed upon us gave us little freedom of action. We gave up the company of 3 RRF because their unit was going too, and we took on board a company of Grenadier Guards instead. They had been stripped out to reinforce 7 Brigade and were a reconstituted company who hadn’t worked together. All the commanders were sent north to fire the 30mm guns whilst the soldiers were sent east to Sennelager to be processed through a well-intentioned sausage machine that was unfortunately outwith my control.

In the meantime the Adjutant had to sort out bums to seats, a procedure which is not easy nowadays because of the degree of specialisation in the modern Infantry: none of our soldiers come out of the backs of their vehicles without some specialist trade: there are no simple load carriers and shit-pit diggers left. During this my headquarters was being engaged in a series of briefings and work up exercises and it became difficult to predict who in the Headquarters was going to be where when. A commander can’t be everywhere at once and there were a myriad of decisions to be taken. I laid down a series of principles: for instance: I want to be administered by the Advance Party not briefed to death: and then left the implementation to everyone else. Mission Command has its place in the office as well as on the battlefield.

As far as manning was concerned the mission was clear: we had to deploy to the Gulf with the strongest team possible: that encompassed selection as well as training. If you weren’t happy about the crew you could either sack people or redeploy them. We did the latter. All Armoured Infanteers have skills, but they were not necessarily doing the job at which they were strongest when the order came. This is the problem with having to operate during peacetime with an organisation designed for wartime: some people are just in the wrong place.

To prepare the Battalion for war we closed down the messes and put everyone on ration strength, feeding the Battalion in the cookhouse. We held a Battalion muster parade before dawn every morning where I briefed the men on what was going on before we all went for an hour’s violent fitness training. The same procedure was repeated before last light (about 1600): more fitness: and then we worked on until we could do no more. Breaking the going-home-for-meals cycle early was important. Soldiers clocked in at home only to sleep. This became a declaration of commitment by the soldiers and their families alike. We made the deadline: just.

Phase 3 : The Deployment. We moved to theatre around Christmas, but this process covered some weeks. During this time clarity of purpose was paramount. Our mission became to deploy to the desert as soon as we could, in order to get on with theatre training. We soon found out though that if you sat about and waited your turn, you would be by-passed. There seemed to be a need to fight for everything. There was also a need to guard your kit jealously, because there were a lot of sticky fingers about itching to relieve you of it. Trust only those you know and keep your beady eye on them. Little worked as planned. What came off the ships bore scant resemblance to the manifest. Although the DOAST (Desired Order of Arrival Staff Table) was meticulously planned, ships overtook each other and some broke down. Planes arrived at strange times and low loaders didn’t turn up. As a result, every hour brought a change of plan, and so, to make the most of what we had got, we decided to deploy piecemeal. Working on the basis that half a company in the desert is worth two in transit, we deployed the vehicles with just the drivers and commanders and then bounced the Jocks into the field to join them within 24 hours of touchdown.

This was now the time to take stock: we were about to go on the offensive in the open desert, not on the defensive in woody old North West Europe, and not with the people we had been training with either. We had also to maintain the aggressive spirit in the Jocks despite the fact that there were few resources available.

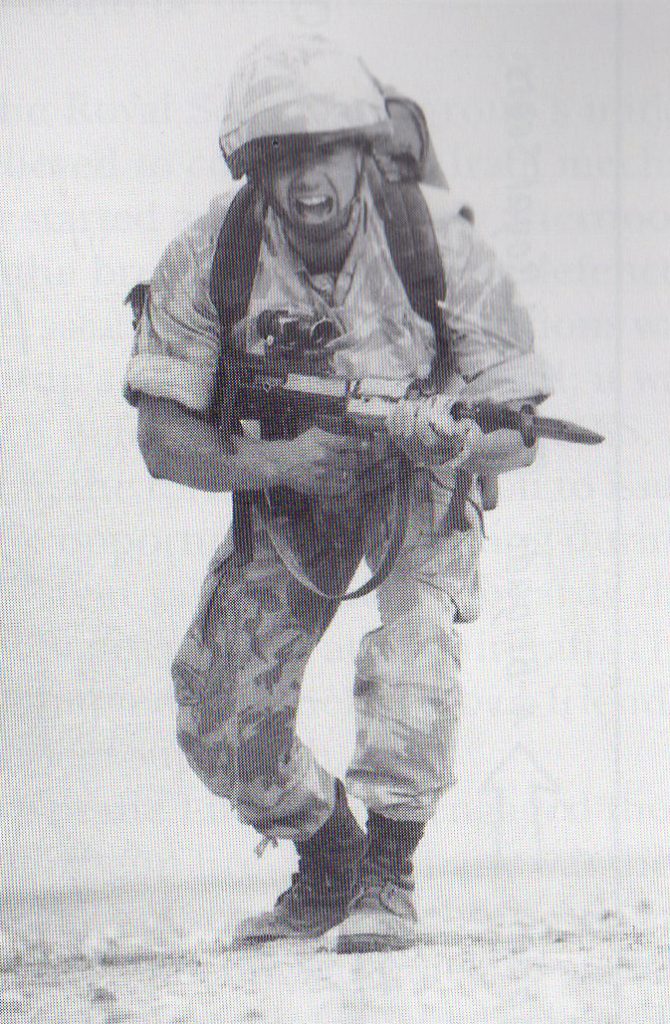

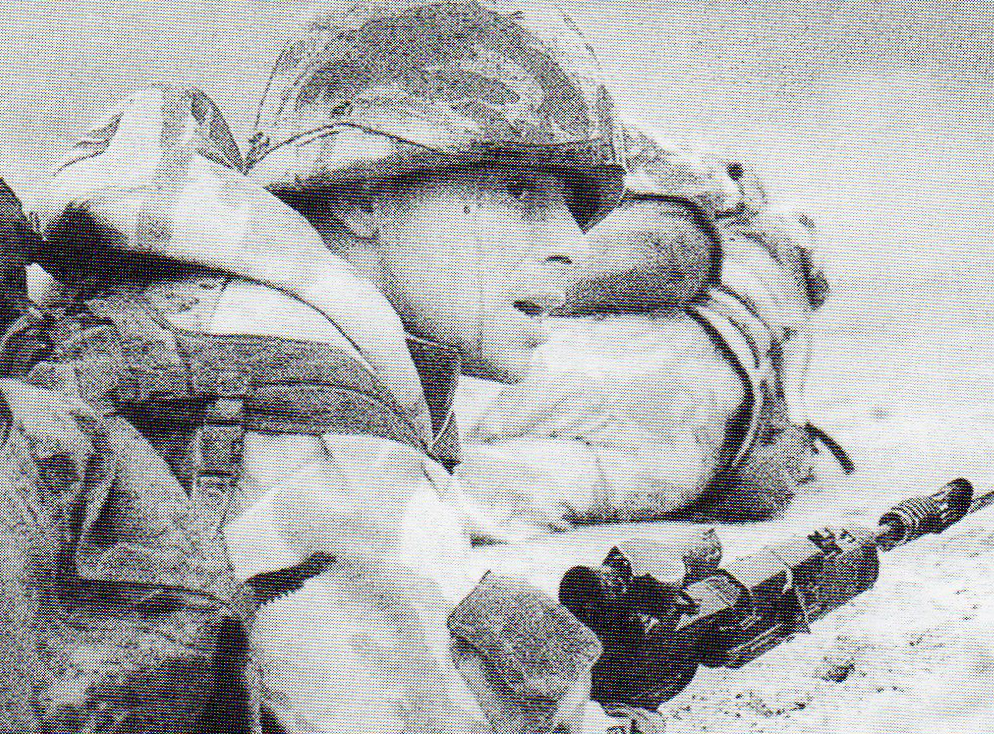

“A reputation of such strength……” Private Owens during the training phase. Private Owens is a grandson of Cpl Elcock VC MM who won his medals with the 11th Battalion in France in the Great War

We had no idea when or indeed if war would start, but we did know that there was no time to waste. We imposed strict standards from the start. People carried all their operational kit all the time. Stand-to was enforced at 0530 and 1800. Light discipline was harsh; Drivers and commanders were forced to drive closed-down wherever they went. Vehicle batteries began to boil in the heat, filling the turret with acid fumes, our remote chemical alarms gave off rogue warnings and we masked in record-beating times while we experimented with numerous measures to reduce sand ingress into the vehicle engines. We were lucky because we had learned much from the STAFFORDS who had been in theatre with 7 Brigade a couple of months longer than we. Never be too proud to take advice. Tempers were lost on an hourly basis in a clash of wills. Slowly but surely the hard posture became second nature, but to maintain it required steadfastness of purpose.

Officers lived with their vehicle crews. There were no perks for them. Everyone was treated in the same way. We backloaded everything that was not essential and then we threw out most of what was left. Bergens (including mine) were shared, leaving a set of clean clothes, washing kit and a notebook as the only personal items. Everything else was communal. The loneliness of command, a somewhat naval concept, had no place in the desert. Personally, it was vital that the vehicle crew knew me, knew when I was tired, knew when I was under stress. I lived with them as a member of the crew and we shared everything. The buddy-buddy system applies as much to officers as to men.

We trained as hard as we could. We had to extract every last ounce of value from the limited resources at our disposal. We set up our own illegal field firing ranges, we scrounged ammunition, we fired day and night and conducted progressively more demanding practices. When one of our company commanders was shot in the stomach during a complex live firing night trench-clearing practice, we were firing again within five minutes of the CASEVAC helicopter taking off. We needed to show everyone that we meant business, and the Jocks thrived on it. They took a pride in the tough image that they were creating and, as the Press began to notice, the tougher they became. They positively revelled in it.

Then at last we began to train with our armour. This was the first time that we had ever worked together and we had a lot of ground to make up: but we were limited in what we could achieve by a shortage of spares and real estate. Everything we used in training would not be available for immediate action. This was a chronic juggling act that must have taxed Div HQ constantly. We had to practise new procedures as well as old: anti missile drills, meeting engagements, counterstrokes and, because we had never worked together before, we had to keep everything as simple as possible. In fact we began to emulate the Soviets, not only in their tactical drills, but in their norms of support as well. There were other problems to address too: the anonymity of the commander was one. It seemed pretty pointless going forward to inspire the troops if they did not know you were there. So, my vehicle flew the somewhat large commanding officer’s Saint Andrew’s flag on its turret (Note. the flag was indentical to the Lieutenant Colonel’s Colour first recorded in 1680!). In the end the whole battlegroup configured on that as a matter of procedure.

Commanding Officer’s warrior in action flying his Colour

At formation level the Div Comander briefed us on the actual plan and then ran it through as a command exercise. This allowed the battlegroup commanders an opportunity to discover potential problem areas, and also gave them the chance to alter procedures.

We then ran through the breaching operation with the 1st US Div (the Big Red One) who were going to make the hole in the Iraqi defences, and practised passage of lines. It was a shambles, but it did allow us to make alterations so that, on the night, the whole thing went like clockwork. Never turn down the opportunity to rehearse. We also used the time to iron out a few misunderstandings at brigade level as well.

General Smith visited regularly and gave us great confidence. He used our operational deployment to the west as a training exercise to practise the plan, so we were becoming pretty familiar with it. This was most reassuring. Talking of reassurance, we had meanwhile been issued with satellite navigation kits, and these proved to be truly wonderful pieces of equipment. Command was suddenly made much easier and every procedure from reorganisation to CASEVAC was speeded up. We split the limited issue of Satnav 50/50 between the teeth and tail. This was a war of logistics, and a REME recovery vehicle with satnav could quickly bring forward a platoon’s worth of refurbished firepower, while spending twice as much time repairing kit, instead of charging around the desert looking for it. There was a deluge of new equipment. We were being given the very best that money could buy and I doubt if any British force has ever been so totally supported. We were given rifle grenades, rocket propelled mine clearers, radar, night viewing aids. We had M548 tracked load carriers to assist resupply, decoy tanks, chemical sheeting and a whole mass of other bits and pieces. Unfortunately we did not have much time to train on it.

Phase 4, The War. We moved up into our forward assembly area. We had been injected against Anthrax and plague (with a whooping cough floater) we had been taking Nerve Agent Protection pills for months. We hadn’t had a drink for ages and my liver thought that it had been transplanted. The Jocks were fitter by not drinking and there had been no discipline cases.

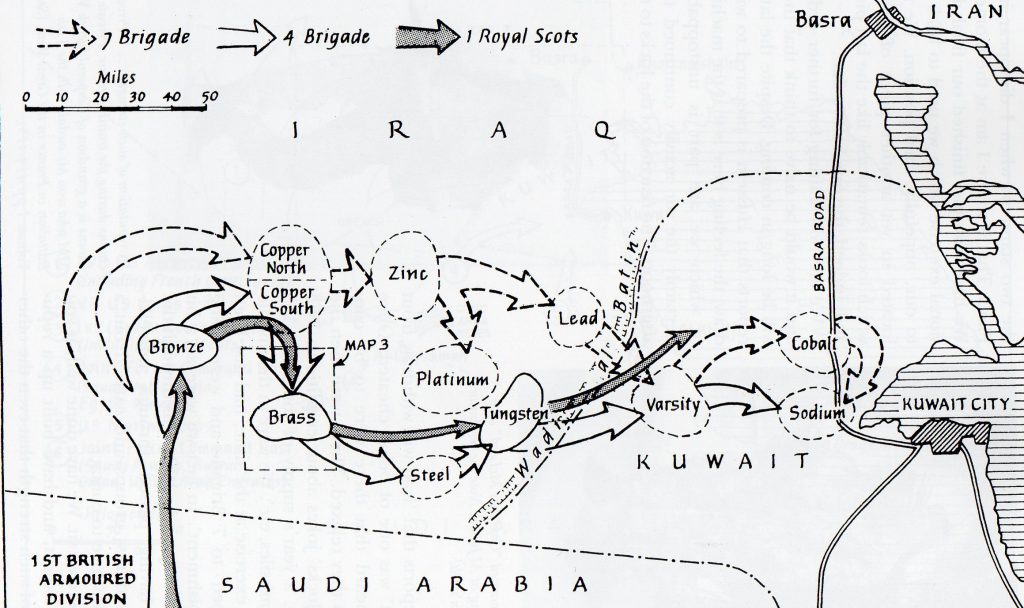

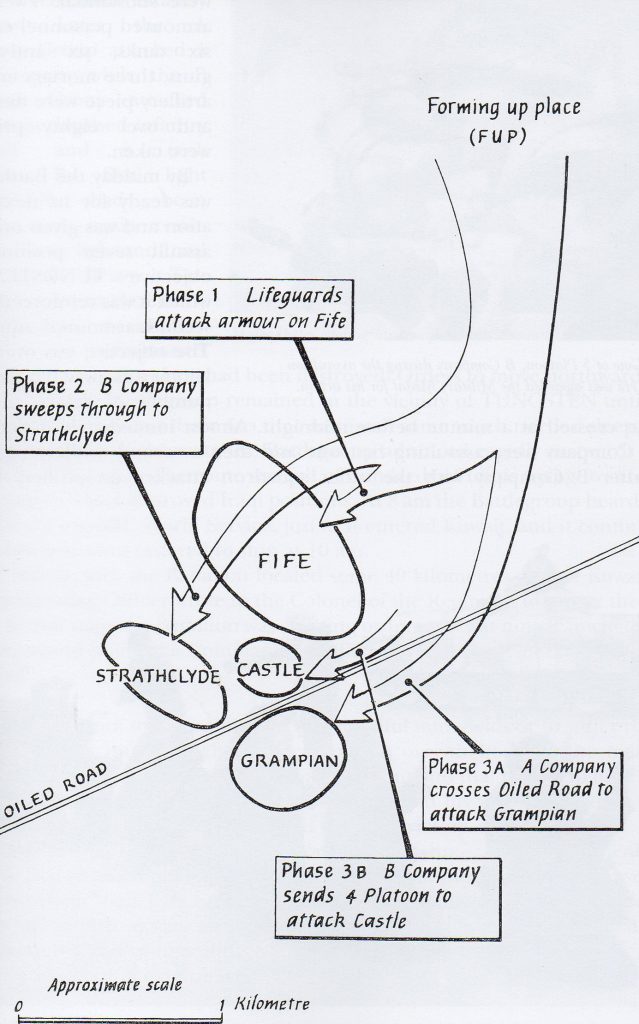

The Brigade was to attack through the US bridgehead to destroy the enemy tactical reserves in order to secure the right flank of the 7 ( US ) Corps. 1RS was to be in reserve initially, was then to destroy the enemy Battalion(-) in the western half of BRASS and was finally to be ready for further moves culminating in the destruction of the Republican Guard. The enemy Counter Attack capability was the initial target. Anything that could move or shoot a long way was to be destroyed.

We were configured as a 1,2 Battlegroup with C Squadron The Life Guards with 15 Challenger tanks, a troop of armoured engineers with CET (combat engineer tractor), bridge layers, mine ploughs and fascines, an ambulance collecting section and a Forward Air Controller under command with up to 2 regiments of artillery in support. The Battlegroup was now over 1000 strong. We moved up to the staging areas and, after it was decided to despatch 7 Brigade first, and after they had gone, we transited the breach. En route to the forming up place the Brigade Commander changed the plan.

1RS were now to clear and destroy the enemy in BRONZE. This had not originally been our task and, to be honest, I hadn’t paid much attention to the detail. And that is another lesson! I tried unsuccessfully to contact all the company commanders on our recently fitted secure radios but their limited issue meant that we didn’t have an all informed secure net and I had to use other means. I held a quick set of orders at the back of my vehicle.

Lieutenant Colonel Iain Johnstone giving his orders. Maj John Potter OC B Coy, kneeling with a notebook, with Maj Norman Soutar OC A Coy to his left. Both were awarded the MC for their leadership in action

Dusk fell. It was a dark, rainy night. Each vehicle showed a red light at the back as an identification feature. That and the lack of ambient light effectively obscured the Warrior’s Image Intensification sights. The Thermal Imaging sights on Challenger, which identify heat sources, worked fine, but they couldn’t see the red lights. Despite the ability of Warrior to match Challenger’s cross country speed, the different sighting systems on that night reintroduced the old divide between armour and Infantry.

H hour arrived. We were expecting to be gassed. We had 3 doctors and 19 ambulances with us and were expecting to take heavy casualties, particularly from artillery and chemicals. We should have been frightened and perhaps we were. As we moved off, the MLRS rockets streaked above us and I offered up a prayer, “Please God don’t let my vehicle break down again”, and we were off.

Immediately we were cut in two by a gunner convoy of over 100 ammunition trucks. Our lead vehicles went off a bit far north and got tangled up with the tail of another unit, the Recce Platoon had a contact to the south and I was concerned that we would get sucked into the very defensive line we were supposed to be bypassing. Sweat was pouring down our faces because we were closed-down and in NBC suits with body armour on top. We moved off in our now so familiar formation and reached Objective BRONZE at midnight.

BRONZE was quite slow. The “clear” mission that I had been given meant that we had to take out every enemy position, and that took time. We destroyed a batch of M46 guns, cleared a string of bunkers and captured about 100 PW.

Iraqi prisoners being rounded up

Hot interrogation outlined the extent of minefields and located the next gun position for us. Leaving B Company to finish clearing up, we moved on using the Lifeguards and A Company. We were accustomed to each other by now and only the minimum of orders were needed.

As we cleared BRONZE we swung north and ran into what appeared to be an infantry position with a large column of armoured vehicles some 2 kms behind it. We were unable to identify them. It was confirmed that there were definitely no friendly vehicles at that grid: we used the gunners laser kit to get a 100% read out but somehow it didn’t have the right feel. We let the armour escape and took out the Infantry position around dawn.

Sometime later we discovered that those unidentified vehicles had been a British dressing station with 30 odd geographically embarrassed armoured ambulances. AFV recognition at long range on TI is difficult. We were now faced with a dilemma. Even though we were under pressure to move on there were quite a few enemy dead and seriously injured soldiers to whom we had a responsibility under the Geneva Convention. The Regimental Aid Post treated the enemy wounded and the padre quickly buried the dead. We loaded the seriously wounded into our ambulances and we set off again. We went due north and then swung down south to take the enemy from the rear on BRASS.

We had actually planned this attack on BRASS. All of the soldiers had been briefed on it in detail. Sitting in the back of a vehicle without any vision ports and without access to the net, with the prospect of launching yourself from it into a well-fortified Iraqi position is not to be envied. The soldiers therefore deserve the very best plan and briefing that time allows. Ours got it. This particular plan had 3 phases: destruction of tanks first, the northern mechanised position next and the southern one last. As we moved off, our heavy artillery fire coupled with strong winds whipped up a sand storm so that visibility was severely reduced. The Lifeguards destroyed the first tanks. There were more than we had expected.

Once the enemy tanks were burning I launched B Company to roll up the right flank. We really had taken the enemy from the rear. Some of his vehicles were dug in so deep that we debussed soldiers to destroy them from the ground. Once the north was secure I launched A Company, who had been creeping down the left flank in anticipation, and they put in their own two-phase armoured infantry assault driving through their own covering barrage so that as it lifted the enemy were at rifle point. About 6 T55, 20 APC, 6 AA guns and miscellaneous trucks, bunkers, stores and ammunition were destroyed. We took another 100 or so prisoners, quite a few of them wounded.

Private Gow of 5 Platoon, B Company during the assault on BRASS. He was awarded the Military Medal for his actions

By this time it was becoming quite apparent that the fight had been knocked out of the Iraqis and that many of them had fled. They seemed to be offering no coordinated resistance. I say seemed because it was impossible to be certain. Unlike other operations this one was so quiet. The commander was cocooned. There was no noise save that of the radios and the throb of the engine. Fighting at night in particular and using the II sights was like playing a computer game on a green monitor with the sound turned down. It was easy to be calm because there was an unreality about it all. It was only when the hatch was thrown back to debus that there was a shock-wave of sound with tracer bouncing off everywhere. You felt safe: too safe: detached from reality. Not an Infantry feeling at all.

Whilst 14/20th and 3 RRF sorted out their objectives, we cleared through the rest of the position. There were a lot of mines and bomblets about, and a number of vehicles had explosions under their tracks. Further orders were called and we were told to take out Objective TUNGSTEN with 3 RRF that night.

The bad news was that, in our northern half of TUNGSTEN, according to the not particularly detailed brief, there were the remains of 2 artillery battalions, 2 mechanised infantry companies, 2 armoured squadrons and an ordinary infantry company at the following seven grid references. Apparently the promised detailed intelligence picture was still in the post. Never believe promises. However, the good news was that the enemy were believed to be significantly reduced. We asked for, and received, an additional tank squadron. It arrived late. Our Recce Platoon, which had been sent forward to identify a crossing point over a pipeline, had become involved in a running contact, and our main headquarters element, which included the mortars and RAP, had been separated from us by a rogue convoy cutting across them. So we were pretty late.

Configuring the Battlegroup as 2 company/squadron groups we crashed over the pipeline from a running start and assaulted one position after the other, rolling across the 17 km objective. It took us until first light to finish and we then swung north into a blocking position. It was all getting a bit too easy and it was tempting to take risks. But what for? We were already moving faster than the Corps could accommodate, and there was the added risk of running into the Egyptians.

We were also terribly tired: a constantly moving operation like this allows no sleep for commanders, and as deputy commanders have to command their vehicles too, they don’t sleep either. The high-tech 24-hour-a-day battle had arrived, and tired people were making small mistakes and took longer to do things. Risk and gain: that is the fundamental equation for all commanders. If there is no gain then take no risk.

We replenished. Our A1 echelon had been tucked up into main headquarters and we had dropped back some MILAN for protection. It carried only ammunition and fuel, the rest was further back. This meant that we were topped up again within an hour or so. In the interim, we had to take out another position, which had been firing mortars. We were getting pretty slick by now, and B Company sorted it out with a fire mission regiment and a platoon attack. We were on the move again that afternoon, but shortly afterwards the tank regiment on our right had a blue-on-blue with the tail end of 7 Brigade and so we were told to hold firm. Thereafter we received a series of orders that were intended to take us north, south and east. Eventually we went east at dawn, in order to cut the road out of Kuwait City, to destroy the remains of the encircled Iraqi army. We stopped some 30 kms short when offensive operations were suspended. For us the short, violent and very successful war had really finished.

Phase 5 : The Debrief. The subsequent spell in the desert was tricky. The place was littered with the debris of war; dangerous debris at that. We reconfigured in a semi non-tactical layout, and suddenly our routine was shattered. The hard tactical posture that had become a way of life had gone and we needed to do something. It seemed silly to train for what we had just done and so we ran a series of cadres in preparation for our Arms Plot move back and during that time we assessed just what, if anything, we had learned as commanders.

The overwhelming use of air power and the stunning logistic success have already been catalogued as operational lessons. From a lower level we learned that IFF needs to be addressed across the whole spectrum, visible and non-visible. We found that PWs, particularly wounded ones, can slow you down. We relearned that people make mistakes when they are tired and that commanders in a mobile war are more likely to get tired than their men. We also discovered that the shift away from an all informed net by using trunk communications or secure radio on limited issue degrades command and inadvertently leaves some people out of chunks of the planning process. We reminded ourselves that the tried tools of command still work: human contact, building trust, ensuring mail gets through, and enforcing firm and fair discipline. Not surprisingly we showed that cutting out booze makes better soldiers and that they didn’t really mind too much provided that it is made very difficult to get hold of.

We also reinforced the point that TD (tactical doctrine) and terminology must be consistent, must be learned and understood by everyone, especially if they’re to be switched between formations. From my command level GRANBY highlighted the need for combined arms training to be conducted on a regular basis exercising with the same units with whom you intend to fight.

There’s no substitute for this intensive field training: because that’s where the sort of problems occur that happen for real. The beauty of DESERT STORM was that it was so similar to our training. The British Army should take comfort from that. However, the prospect of ever diminishing opportunities to carry out such field training in the future is concerning. It will have repercussions for commanders and subordinates alike. It might even encourage Lindt’s “zero defect mentality” where commanding officers, given only one chance at jumping through the hoop might become less prepared to allow their subordinates any opportunity to make mistakes. That would lead us down the path towards rigid centralised control: a dangerous path for all that. Things happen so fast in this high tech environment that rigid centralised control can’t keep up, as the Iraqis discovered.

I said at the very beginning that command in war was easy. This is perhaps not surprising as we had been given time to conduct work up training before we launched and, once we did we had air supremacy, significant reinforcement, the best equipment and the very best of soldiers. We also had tremendous support from our Army and our Public. Despite the fact that we had transited minefields, attacked an enemy who was reported to have 125 brigades of war hardened troops and one who would not hesitate to use chemical weapons, we suffered virtually no casualties. We were outstandingly lucky. We were luckier still to have been part of such an overwhelming success because nothing makes command easier than success.

Oil by David Rowlands painted in 1991 for the Warrant Officers and Sergeants Mess