2nd BATTALION THE ROYAL SCOTS (2RS) WITH THE BRITISH EXPEDITIONARY FORCE (BEF) IN FRANCE

AUGUST TO MID-NOVEMBER 1914

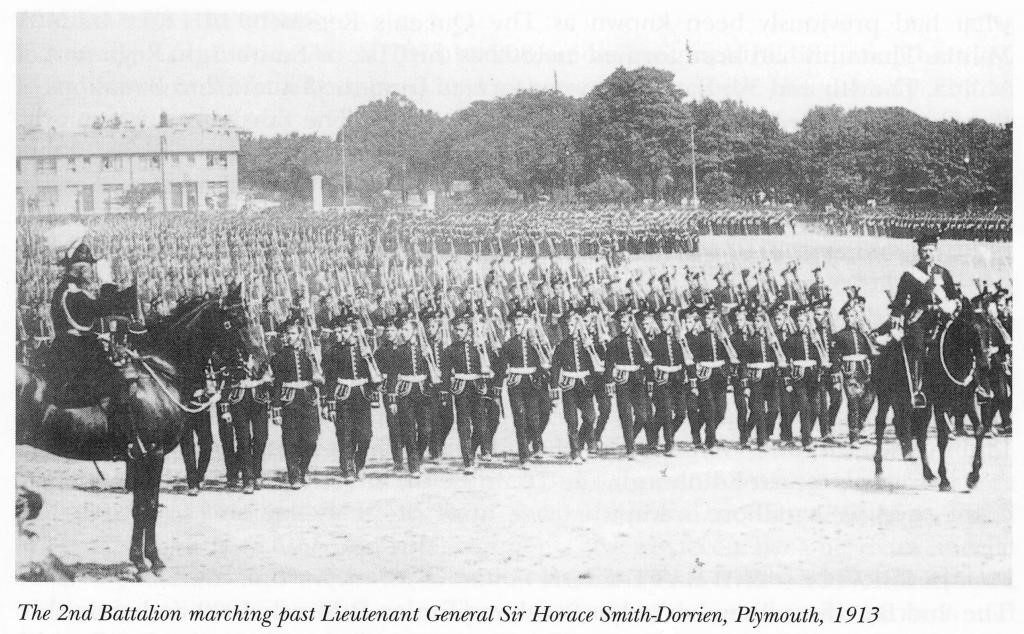

Before the Storm. General Smith-Dorrien was to be 2RS’s Corps Commander in the BEF.

Preparation and Deployment

2RS were on annual field firing training when it received instructions on 29 July 1914 to return to its barracks in Plymouth. The order to mobilise arrived on 4 August and measures were immediately taken to bring the Battalion up to its war establishment of 30 officers and 972 other ranks. In 1914 a battalion was organised with a Headquarters, including a machine gun section of two Vickers-Maxim guns, some horse-drawn transport and the band, and four companies of six officers and 221 soldiers, each consisting of four 50 strong platoons divided into four sections. On 6 August three officers and 160 soldiers joined from 3RS, the reserve regular battalion, and the following day some 507 reservists, ex-regulars with a reserve liability, reached 2RS in Plymouth, followed, on the 8th, by a final draft of 50 regular cadre from the Depot and a few more reservists. The Battalion, now more than double its pre-war strength, reported ‘ready to go’ on the 9th. Finally, on the 10th, ‘peace details’ of two Officers and 160 moved to join 3RS who were now at their mobilisation station in Weymouth. The whole mobilisation operation, taking under a week, had gone extraordinarily smoothly and efficiently considering the numbers involved moving around the country, lack of media communications (radio, TV and telephones) in those days, and the distance many of the recalled reservists had to travel.

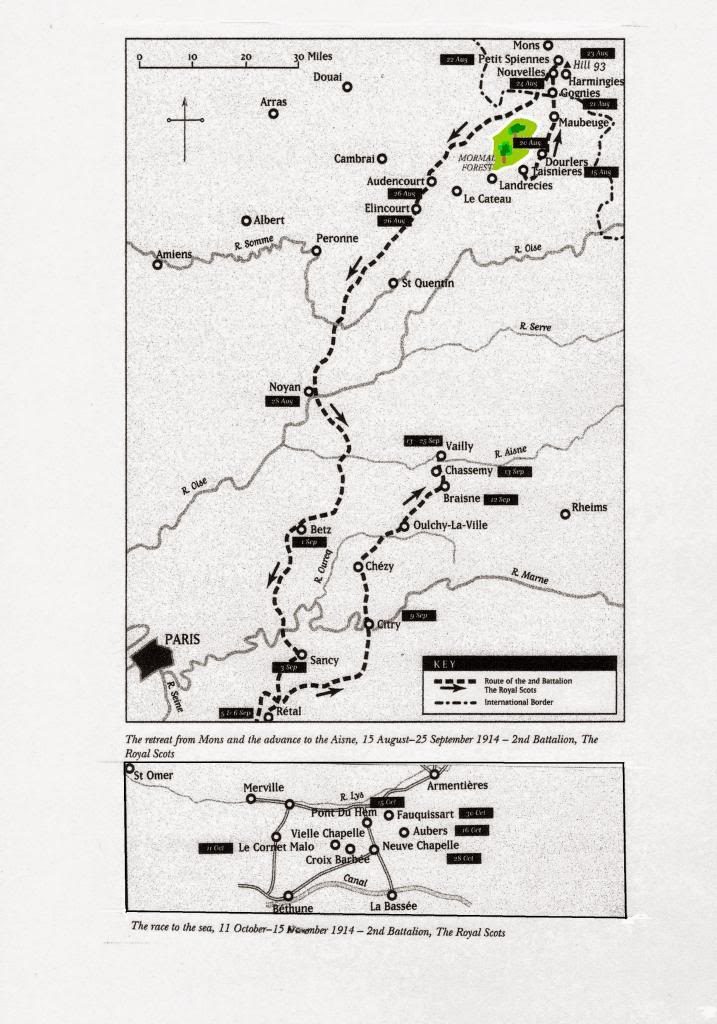

With all arrangement complete, reservists joined their companies and began training on the ‘short’ Lee-Enfield rifle (SMLE), which had recently replaced the ‘long’ version, as well as improving their fitness through route marches and PT. Orders to move were received on 12 August and, the following day, two trains carried 2RS to Southampton where it embarked on the SS Mombasa, sailing that evening for Boulogne where it disembarked early on the afternoon of the 14th. The warmth and exuberance of the welcome the Battalion received was overwhelming. It formed up with difficulty and, with the pipers playing La Marseillaise, marched off to spend its first night in France at a rest camp. The following day it entrained for the BEF concentration area which lay between Le Cateau and the fortress town of Mauberge, just south of the Belgian border (see the map at the end). 2RS were billeted in the village of Taisnieres where, over the next few days, a mixture of route marches and other training further helped the reservists integrate with their regular counterparts.

On 20 August, barely two weeks since the declaration of war, the BEF, some 100,000 strong, was complete in its concentration area. It was divided into two corps (three from 31 August) each of two infantry divisions. These, in turn, comprised three, four battalion, brigades. There was also a 9,250 strong cavalry division and a further independent cavalry brigade, plus Army-level troops, including five squadrons of The Royal Flying Corps. That day orders were given for the whole force to advance into Belgium, on the left of the French Fifth Army. 2RS was in 8 Brigade, 3 Division, which was part of 2 Corps. The Battalion marched to billets just short of the Belgian border that day and, on the 21st, crossed the border receiving a token formal protest from the few Belgian soldiers on duty manning a barricade there. There was no news of the enemy but the soldiers suffered greatly during the day (and over the next three weeks) from the intense heat and the cobbled roads, which made marching a real test for the feet. Matters were not helped by the locals ‘forcing’ bottles of wine and fruit on the passing Jocks! On the 22nd the Battalion marched to Petit Spiennes, a few miles south of Mons and, on the 23rd, were ordered to prepare defensive positions against the advancing Germans.

Mons, Le Cateau and the Retreat from Mons

2RS’s position, on the right of the Brigade, was along a 2 ½ kilometre section of the Mons-Harminges road, with the prominent feature of Hill 93 on its right flank. This was a longer frontage than normally allocated to a battalion so the reserve had to be reduced to only two platoons. The main German assault fell on the left of the Brigade position leaving 2RS relatively undisturbed during the morning , during which they improved their positions. During the afternoon, however, the Germans mounted an attack on Hill 93 which was driven off, with heavy losses, by the accurate rifle fire of the defenders. The Battalion was reinforced by two companies of The Royal Irish at around 4 pm, ahead of a further strong German attack between 7 and 8pm. Again accurate rapid fire drove them back and no further effort was made to take the position. The Germans, however, had made progress through Mons itself and this threatened to outflank the 8 Brigade position. At about 10.30pm the Battalion was warned to prepare to withdraw. This was successfully accomplished in the early hours of the 24th, 2RS being the last unit in 3 Division to withdraw. Total casualties that day, in which considerable losses had been inflicted on the Germans, were two wounded and four missing.

The next two days were spent withdrawing to the south-west under a blazing sun which left all of the Battalion parched with thirst. Pursued by the Germans, there was little rest until, having passed to the west of Mormal Forest, they came to the area of the village of Le Cateau on the evening of the 25th. The original plan was to continue the retreat, starting before dawn on the morning of the 26th. With some troops only arriving in the area at 2 am, however, and the route out of the Le Cateau area dominated by a ridgeline to the north-east which, if not held by our own forces when day broke would have meant the withdrawal would have been in full view of a much stronger enemy force, the decision was made to stand and fight. The Battalion’s position was near the centre of 2nd Corps whilst most of the action during the day was against the flanks. By 2 pm, however, major attacks were developing on the boundary between 2RS and 1GORDONS to their left, but, as at Mons, the enemy were kept at bay by the withering and very accurate fire that was the hall-mark of the BEF’s professional infantry, firing bolt-action, magazine-fed rifles. Two platoons of D Company reinforced the Gordons during this battle. 2RS held their position until 4.30 pm when they were ordered to withdraw, a manoeuvre which had to be accomplished in full view of the enemy leading to its heaviest losses during the day. These, amongst the officers, were one killed and three wounded, including the Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Colonel McMicking, who, severely wounded, had to be left behind. A further nine officers were reported as ‘missing’ although two of these, with small parties of soldiers, rejoined the following day. One was later confirmed as killed, three others were found to also have been wounded but evacuated and two more eventually rejoined the battalion on 8th September having been with other units since Le Cateau.

In the confusion of the withdrawal it was not initially known how many soldiers had been killed, wounded or were missing, although an examination of the post-war casualty lists suggests a figure of 24 were killed that day, a total of 175 had been captured, including some wounded, and 30 were missing. D Company was reduced to a strength of one officer and seventeen soldiers, against their establishment of six and 221. This was partly due to the fact that the Gordons, still with the two D Company platoons under command totalling some 100 men, never received the order to withdraw, remaining in position until dusk fighting off German attempts to follow up on the withdrawal. Their action and the price they paid later, having been surrounded and most of the battalion, including the two platoons of D Company, taken prisoner, allowed the rest of the Division to withdraw, under the very eyes of the enemy, with surprising ease and, under the circumstances, without disproportionate losses. A further ‘casualty’ in the action was the loss of the Battalion’s transport, including the Pipes and Drums instruments which were on it, to German shelling of the village in which the waggons had been harboured. Not everything was destroyed however, as, in 2014 while reorganising a display with the Museum we found an inscription on a plaque on an old bass side drum which reads “Carried by 2nd Bn The Royal Scots during The Great War and into Germany 1914-1919”.

By nightfall on the 27th the German pursuit had been shaken off and, although the Battalion continued to withdraw under a blistering sun during the day, and with little opportunity for rest at night, matters became slightly better. Major John Ewing, in his two volume history of the Regiment in the 1st World War, described the days immediately after Le Cateau, as groups of soldiers, often from a variety of cap badges, sought to rejoin their own units as ‘organised disorganisation’. The BEF was a professional army with immense reserves of physical stamina and mental determination. The retreat from Mons was never in danger of becoming a rout. Ewing attributes this to the fact that ‘The whole peace-time training of the British Army had been directed to teach the men to organise themselves, when there was no officer to do so, and the immense value of this training was never better exemplified than during the retreat from Mons.’ Further evidence that this was a remarkably disciplined and controlled ‘rearward movement’, is shown by the fact that, on 29 August, the Battalion received its first mail from home since arrival in France. To escape the fearsome sun which continued to beat down, some soldiers discarded their glengarries, which offered little protection, in favour of the broad brimmed straw hats usually worn by French peasants. Others put cabbage, or marigold, leaves under their glengarries to provide some cover.

The withdrawal continued through to 5 September when the Battalion arrived at Retal, some twenty-five miles south-east of Paris. During the previous twelve days 2RS had fought two holding battles and marched 140 miles. Since the stand at Le Cateau, the sun had proved a much more intractable enemy than the Germans. Significantly, however, both the BEF, and the French Fifth Army on their right flank, had escaped from encirclement by the German right flank. The stage was now set for the BEF to move onto the offense.

The Advance to the Aisne

2RS, having received its ‘first reinforcements’ (Battle Casualty Replacements or BCRs in today’s language), left Retal at 6 am on 6 September, marching north and east for the next two days. On the evening of the 7th the ‘second reinforcements’, of one officer and 93 men, joined the Battalion. At 5 am on the 8th it moved off heading north: by 10 am it was being shelled, but the advance continued, despite some resistance from enemy infantry, and the Battalion took 160 prisoners during the day against a loss of some 25 casualties of their own. On the 9th 2RS advanced to Citry on the River Marne. It experienced some shell fire but there were no casualties and it crossed the river unopposed at 7 pm. The War Diary for that day records that Lieutenant MacLean, who appears to have been serving with the Royal Flying Corps, ‘was doing aerial reconnaissance work at Citry.’ This is the first record of an airborne Royal Scot on active service. Over the next three days the Battalion saw no action as it advanced to Braisne, just six miles south of the Aisne. The major difference from a week earlier, other than advancing rather than withdrawing, was that the weather had changed to heavy rain leading to muddy, churned up roads which slowed the advance.

The high ground on the north bank of the Aisne, now occupied in strength by the Germans, dominated the BEF’s approaches to the river. On 13 September, 2RS, with 8 Brigade acting as the Divisional vanguard, and having been subjected to artillery bombardment, closed up to the Aisne by 10 am to find that the Germans had destroyed both the railway and main road bridge on the 3 Division front . Near the destroyed road bridge, however, they found a narrow plank with ropes attached to it stretched across the river. The Germans in their earlier haste to withdraw had failed to pull the plank away. Wasting no time, Lieutenant Colonel Duncan, now commanding the Battalion, pushed A and C Companies across the rickety and perilous route. They were followed by The Royal Irish and by 3 pm a small bridgehead had been secured. By 6 pm the remainder of the Battalion had crossed to be followed during the night by 9 Brigade. During the night a German patrol of an NCO and fifteen soldiers was captured by A Company. At dawn on 14 September the Battalion attempted to continue its advance onto the high ground to its front. It quickly came upon the main German defensive position, which in spite of a number of local, company-sized actions, could not be penetrated. Eventually, running low on ammunition and with casualties increasing, including Lieutenant Colonel Duncan, whose horse had been shot from under him, the Brigade withdrew to a line on a low ridge just north of the original bridgehead where it initially established a line of rifle pits, each containing a few men, rather than the continuous and complex trench lines, including various support lines and communication trenches, which developed later in the war.

The Battalion remained in position, improving and connecting the rifle pits into a basic trench line, until 25 September during which time it suffered considerable casualties. Captain Price, the Adjutant, was killed amongst a total of 25 casualties on the 16th alone. Many of these casualties resulted from German artillery fire – although the rifle and, increasingly, the machine gun was still the chief weapon of the infantry, for the army as a whole the artillery was now assuming an importance it had never previously held. Much greater effort was required in digging trenches providing protection against shellfire. The strain on individuals gradually relaxed as reinforcements arrived, one officer and 100 soldiers on the night of the 19th and a further one and 150 on the 22nd, but the wet trenches and, now, piercing coldness of the nights played havoc with general health and several men had to be evacuated to hospital. Finally, on 25 September, the Battalion was relieved. It withdrew back across the Aisne and marched to Courcelles, some seven miles to the south, where it remained in billets until the end of the month. All was not rest, however, as the War Diary records on Sunday 27th, ‘Church Service (voluntary) held in the morning by the Rev Meek: a small number of men attended’; and the following day, ‘General Smith-Dorrien [Commander 2 Corps] expected to inspect 8 Bde in the morning, but did not arrive. Men told to be in readiness during the day. All billets to be perfectly clean. Later in the day heard General’s visit postponed till the next day.’ He eventually arrived at 1 pm on the 29th!

Church service in the field

The Race to the Sea

By the end of September it was clear that neither side was going to make any significant progress on the Aisne. The only direction in which there was scope for manoeuvre was northwards, towards the strategically important Channel ports. In early October the BEF was moved, in strict secrecy, to the area to the west and south of the town of Ypres in Belgium.

During the first ten days of October the Battalion, under Captain Croker, by then the senior officer, moved North, on a circuitous route, travelling by night, and remaining out of sight by day. Most of the distance was covered on foot, but trains and motor transport were also used on occasions. Marching proved a severe test to the feet after the long spell in wet trenches and many men fell out over the first few days. That together with a number of cases of drunkenness was commented on at a Battalion parade addressed by the Brigade Commander on 7 October. On 10 October the Battalion was reinforced by the arrival of two Captains and seven Second Lieutenants. On 11 October the Battalion arrived at Le Cornet Malo, just north of Bethune and some 90 miles north of Courcelles, their start point, where it replaced a French cavalry unit. The area is the ‘Black Country’ of France. The land is flat and soggy, almost without cover and criss-crossed with broad, deep dykes while numerous mining structures and cottages provide strong points from which a determined enemy could only be driven at considerable cost to the attacker.

On the 12th the Battalion received orders to advance north-east to secure the Pont du Hem – Neuve Chapelle road. The going was very difficult over the open water-logged country and they suffered over 70 casualties including three officers. Ewing makes the comment that the Battalion ‘had been operating against an enemy whom they could not see and who, well supplied with motor cars, moved off to a fresh post whenever The Royal Scots came within striking distance.’ While similar to the tactics of the Boers using their ponies to retire from the kopjes dominating the open veldt of South Africa fifteen years earlier, it was probably one of the earliest uses of motor vehicles in the front line. The 13th and 14th October were no easier with little ground gained towards the objective and, again, heavy casualties taken. On the 13th two officers were killed, both of whom had been amongst the reinforcements who had arrived three days earlier, and a further five wounded. On the 14th, Major General Hamilton, GOC 3 Division, was killed by a sniper while walking along a road in sight of the enemy. While proving that Generals did not sit back remote from the action, as some authors have suggested, it also proved that they, like ordinary soldiers, were not immune to bullets. By the evening of the 14th, with two more Captains wounded that day, only subaltern officers were left in the Battalion and, on the 15th, Captain G Thorp, an Argyll and Sutherland Highlander serving as a staff officer at 8 Brigade, temporarily took over command of the Battalion. Pushing forward against considerable opposition, the attack was again brought to a halt, this time as darkness fell, still some 500 yards short of the objective set for 12 October. Brigade, however, ordered that the road had to be secured that day. A night attack was therefore launched and, to everyone’s surprise and relief, reached the road at about midnight without encountering any opposition. Fifty-three soldiers are recorded as having been killed on the 15th, although it is appears likely that that total covers the four days of the action.

8 Brigade, with 2RS, moved into reserve on the 16th, and the next day, with Major Dyson now in command, the Battalion marched to Aubers where they moved into billets. On the 18th, due to German shelling, the Battalion had to withdraw from the village to a field outside. The War Diary records the seemingly important information that ‘Also GOC’s two chargers [horses] killed’! On the 19th the Battalion moved forward into a firing line about ¾ of a mile east of Aubers, where they remained until the night of 22/23 October when the Division withdrew to the line of the Fauquissart – Neuve Chapelle road covered by the Battalion who themselves then withdrew. The following night the Battalion fired on a large party of Germans who were patrolling close to the front line and drove them off. About two hours later several hundred Germans successfully attacked 1GORDONS on the Battalion’s left, driving them from their trenches. The sounds of that encounter, ‘cheering, shouting, trumpet calls etc’, alerted the Battalion which changed its dispositions to protect its left flank. Later the Germans made an attempt to storm the Battalion’s trenches but were driven off by concentrated rifle and machine gun fire, the latter from one of the Battalion’s two machine guns which had just been redeployed, under fire, to cover the flank.

Patrols were sent out to discover what had happened to the Gordons but their trenches were found to be unoccupied, apart from dead and wounded Germans and Highlanders. In due course 4th Middlesex, the reserve battalion of 8 Brigade, took over the Gordon’s trenches and the situation was restored. The position might have been much more serious had the Battalion not reacted so determinedly both to the initial German probe and the later threat to its flank. The War Diary estimated that 75 of the enemy were killed with several taken prisoner. 2RS’s losses were one officer killed and one officer and seven soldiers wounded. The following day was tense with incessant rifle and artillery fire during which several officers and men were killed or wounded. The War Diary reported ‘heavy rain all night, many rifles rendered useless on account of mud jamming the bolts.’ Four Captains from The Border Regiment joined to replace some of the Battalion’s losses.

On the 27th the Battalion was relieved in the front line and moved into reserve trenches from where it prepared to support a battalion of Sikhs who were to make a night attack on Neuve Chapelle. That attack was postponed and, instead, 2RS were ordered to take the village the following day. The attack started at 1 pm and soon came under rifle, machine gun and artillery fire. Before leaving our own lines, however, the Battalion was ordered to stand fast and occupy trenches and, at 6 pm, to fall back to a new position at Pont Logy where it endured further shelling. On the 30th the Battalion was relieved and moved back to Fauquissart where it occupied the former trenches of the Gordons and where it received further reinforcements of one officer and 115 soldiers. On 2 November the War Diary noted ‘Germans evidently thoroughly understand our method of signalling [during range firing practices] as they signal back “misses” with a long pole to each shot fired by our snipers’. (Who said the Germans have no sense of humour?) The Battalion continued to occupy trenches in that area throughout the first half of November but, by then, the intensity of the action had subsided. The ‘Race to the Sea’ was over. Europe was now divided by a continuous line of trenches running from the English Channel to the Swiss border and both sides settled down to what was to be four years of slogging trench warfare at a terrible cost in human lives.

Summary

Undoubtedly 2RS had made an auspicious start to the Great War; again without doubt it had been lucky. By the end of the year the BEF, by then seven infantry divisions strong, had sustained some 90,000 casualties, a figure matching the original force that had landed in France in August, and one-third of the original force was dead. The omens for the future were ominous. During the first Battle of Ypres, subsequently known as the graveyard of the BEF, which officially came to an end on 22nd November 1914, the casualties totalled 50,000. Of the fifty-two battalions that had landed in France in August few could muster more than 300 men by the end of the year, and eighteen were reduced to fewer than 100. By comparison 2RS, which had been reinforced steadily across the period by over 600 officers and soldiers, a further clear demonstration of the administrative efficiency of the BEF even during intense operational movements, remained viable – as shown below.

In the period from arrival in France to 15 November 2RS suffered the following known casualties: Officers: Nine killed and 22 wounded with one missing – probably one of the D Company platoon commanders attached to 1GORDONS at Le Cateau, the other was killed. A total of 31 casualties against a war establishment of 30 or, in other words, over 100% casualties in less than three months. Soldiers: 144 killed. There is virtually no information on numbers wounded but, if the same ratio of wounded to killed for the officers is used, the figure would have been 351. This gives a total of 495 casualties or 51% of establishment. 215 were listed missing, of which 193 were known to be POWs. Reinforcements: Over the period 5 September – 30 October 2RS received 25 Officer (12 Captains and 13 Subalterns) and some 600 soldier reinforcements. If the casualty and ‘missing’ figures above, based on the best information available today, are accurate, the Battalion strength in mid-November 1914 would have been around 24 officers (-6) and 862 soldiers (-110) although that is probably a bit high.

Battle Honours

The Regiment was awarded the following Battle Honours in recognition of the 2nd Battalion’s actions over this period. Mons, LE CATEAU, Retreat from Mons, MARNE 1914, Aisne, La Bassee 1914 and Neuve Chapelle. The Honours LE CATEAU and MARNE 1914 were subsequently chosen to be amongst the ten to be carried on The King’s Colour.

Retreat from Mons