The Territorial Battalions in WW2 From Walcheren to Bremen and Normandy to the Baltic

In September 1939 the Regiment had three Territorial Battalions all of which were mobilising, the 4th/5th (Queen’s Edinburgh) manning searchlights, the 7th/9th (Highlanders) and the reforming 8th (Lothians & Peebles) both in the infantry role.

4th/5th Battalion (Queen’s Edinburgh Rifles)

The 4th/5th were in fact the first battalion of the Regiment to see action being engaged in the first air raid of the war when the Luftwaffe tried to bomb the Forth Bridge on 16 October. On 23 October, the first enemy aircraft to be shot down crashed near Humbie in Midlothian near a 4th/5th detachment who took the pilot prisoner- the first German of the war to be captured. He had no doubt that the war would be over by Christmas and he would be home in Germany! The 4th/5th were converted to the anti-aircraft role and on 1 August became a Regiment of the Royal Artillery but proudly retained their Queen’s Edinburgh connection. This was strengthened in December 1944 when the reformed 1st Battalion, serving in Burma, received ninety-nine, particularly welcome, reinforcements from 405 Searchlight Battery, formerly part of the 4th/5th!

7th/9th (Highlanders) Battalion

The 7th/9th Battalion, as part of 52nd (Lowland) Division, mobilised in September and deployed on coastal defence duties on the Forth based around Kinghorn in Fife. From there it moved to the Dumfries area and, in May 1940, to the south of England in preparation for deploying to France. As the month progressed, however, the news from there became progressively worse culminating in the evacuation from Dunkirk. To bolster French resistance it was decided to send the Division to France and the Battalion sailed from Southampton to St Malo on 12 June – nine days after the last troops had been evacuated from Dunkirk. On arrival the Battalion moved to a position near Le Mans, eighty miles south-west of Paris only to be told to immediately return to Britain, Despite the proximity of German troops and aircraft the Battalion was able to leave Cherbourg on the morning of 17 June less than a week after they had landed. There were no casualties, but all the Battalion’s transport, less eight of its nine carriers which were successfully loaded onto a ship, had to be destroyed before embarkation.

On arrival back in England the Battalion reformed in East Anglia with the role of anti-invasion and airfield defence. After 6 months, with the Battle of Britain won, the Battalion returned to Scotland where it moved successively to Alloa, East Lothian, Bridge of Allan and, finally, Peterhead/Cruden Bay. In the autumn of 1942 the Division began to train for possible operations in Norway. This involved learning to work with mules, mountain training and long arduous exercises in the Cairngorms in all types of weather. This training continued throughout 1943.

The 7th/9th Battalion training in the Cairngorms with an Indian Army mule team

The winter and spring of 1943-44, when snow conditions were fairly severe, saw the completion of the Battalion’s mountain training with long periods living in the mountains on major exercises, skiing, handling of loads on pack horses and sledges drawn by both men and dogs. The Division was now classified as ‘Mountain’ and added that flash below the Divisional badge. In May 1944 the Division moved to Inverary for combined operations training. There was bitter disappointment when D-Day passed and the Battalion was not called on to play an active part in events.

All was to change, however, when the Division was placed under command of First Allied Airborne Army as an air transportable unit. Scales of transport were considerably reduced and all ranks had to become familiar with the intricacies of loading aircraft with everything needed for operations. As soon as these skills had been learnt the Battalion moved south to Buckinghamshire. From then onwards it was either at twenty-four or forty-eight hours notice to board its aircraft and join the war in Europe. Several operations were planned and were on the point of coming to fruition when they were cancelled, largely because by then operations on the ground, following the breakout from Normandy, were moving forward faster than expected, A total of four such operations were cancelled in the months of July and August. In September the Division was due to take part in the Arnhem operation as soon as a landing ground had been secured but, with the failure of the initial phase of the operation, the Battalion’s fifth and final planned air landed operation was cancelled.

With the approaching autumn weather precluding any possibility of further air operations, 52 (Lowland) Division reorganised yet again, this time as a conventional infantry division, and prepared to move by sea and to come under command of the First Canadian Army for operations in the Scheldt Estuary. On 16 October the 7th/9th embarked at Southampton for Ostend. On 3 November the Battalion was launched in the assault on Flushing on the Island of Walcheren at the entrance to the Scheldt leading to the key port of Antwerp. Most of the Island was flooded, the sea walls having been breached by a mixture of RAF bombing and German demolitions. It was a curious and ironic twist of fate that the Battalion, after all its long years of training to fight on the mountain-tops, and being carried to war through the air, should eventually enter battle through an amphibious operation below sea level!

General Daser being led away by Major John Knox RA, Brigade Major 155 Inf Bde after surrendering to A Coy 7/9RS'

German prisoners in the town square

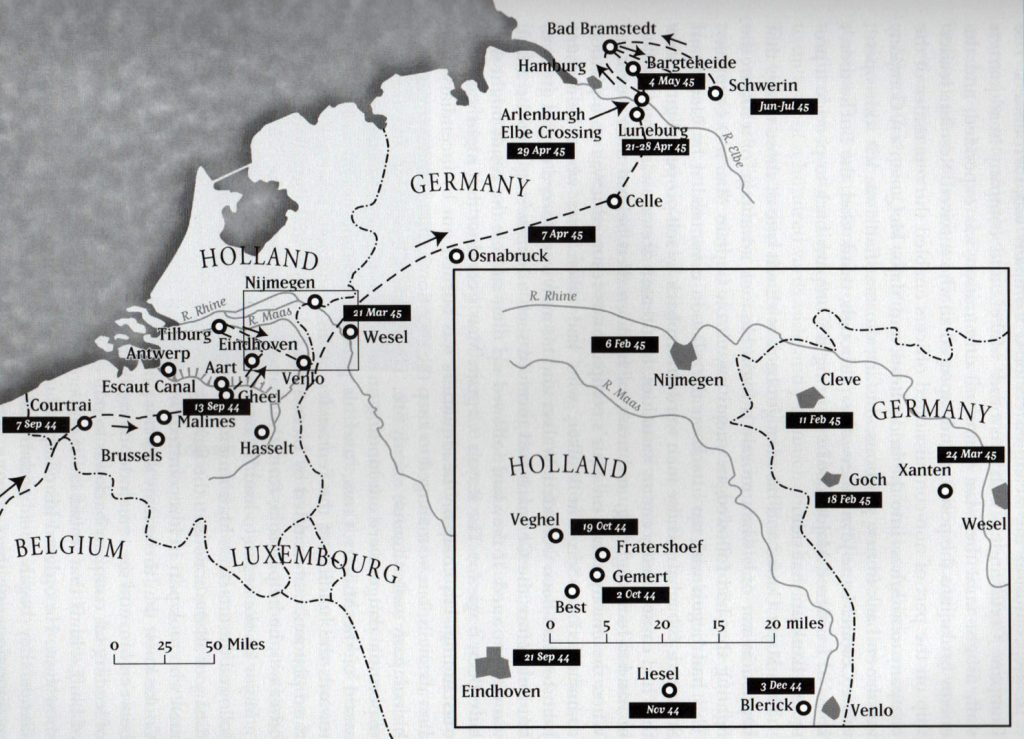

Route of the 7th/9th Battalion 18 October 1944 -5 May 1945

During the winter the Battalion was involved in Operation Blackcock holding the Heinsberg salient near Maastricht to clear the last German pockets of resistance on the west bank of the Maas. This was finally achieved with a pincer attack on the town, in conjunction with 4 KOSB, on 24 January 1945. In mid-February, with a Dutch company under command, the 7/9th moved north to Gennep, on the River Maas. It was committed to operations in the Broederbosch, a forest of many thousands of acres. The main objective was Kasteel Blijenbeek, a medieval Durth fortress close to the German border. The Battalion closed up to it but, in daylight, found the Kasteel, and the high ground behind it, completely dominated the whole of the surrounding area and any movement attracted heavy and accurate fire. The walls of the Kasteel proved impregnable to 25pdr shells and a company attack by the KOSB had to be called of because of the loss of so many supporting tanks. Eventually the RAF were called in and, with the aid of 1000lb bombs and rocket-firing Typhoons, the Kasteel was eventually abandoned and the Battalion, which had suffered 44 casualties in a week, were withdrawn.

By early March they were poised at Xanten on the Rhine. After crossing the Rhine on 28 March, meeting the 8th Battalion en route, 155 Infantry Brigade, of which the Battalion formed part, came under command of 7th Armoured Division, ‘The Desert Rats’, to spearhead the breakout from the bridgehead. It remained with them until the closing stages of the campaign. In a rapid advance across Germany they cleared the Teutoburger Ridge, secured Barnstof and ended up in Soltau on 17 April, which they captured after a stiff battle supported by tanks and flame-throwers. Rejoining 52 (Lowland) Division they played a major part in the taking of Bremen and ended the war garrisoning that port.

8th (Lothians and Peebles) Battalion

Following Hitler’s seizure of Czechoslovakia in 1938 the Territorial Army was doubled in size and the 8th Battalion was reformed, with much help from the 7th/9th Battalion. By July 1939 it had reached a strength of 500 and it was officially established on 1 August. On the outbreak of war, the Battalion initially moved to the area of Earlston and Lauder where it continued to build its strength and develop its military skills. By December it was considered fit to relieve the 7th/9th Battalion on Forth Defence duties. In April 1940 they moved to Galashiels and then, as the German attacked through Belgium, down to the south of England where they moved around, as part of 15th (Scottish) Division, on anti-invasion roles until the end of 1941 when they moved to the Northumberland coast and were put on Lower Establishment which meant they had to supply drafts to units going overseas.

In April 1943 Lieutenant Colonel Delacombe took command, shortly after the Battalion returned to the Higher Establishment and the Division was joined by the 6th Guards Tank Brigade. Colonel Delacombe was a ferocious trainer of both individuals and the Battalion as a whole as the tempo increased throughout 1943 and into 1944 with the approach of the invasion into Europe.

The 8th Battalion landed in Normandy on D+10, 16 June 1944. They were soon in action with 15th (Scottish) Division in establishing what became known as ‘The Scottish Corridor’ with the aim of relieving German pressure on the Americans to the west by securing a crossing of the River Odon and into the area to the south of it.

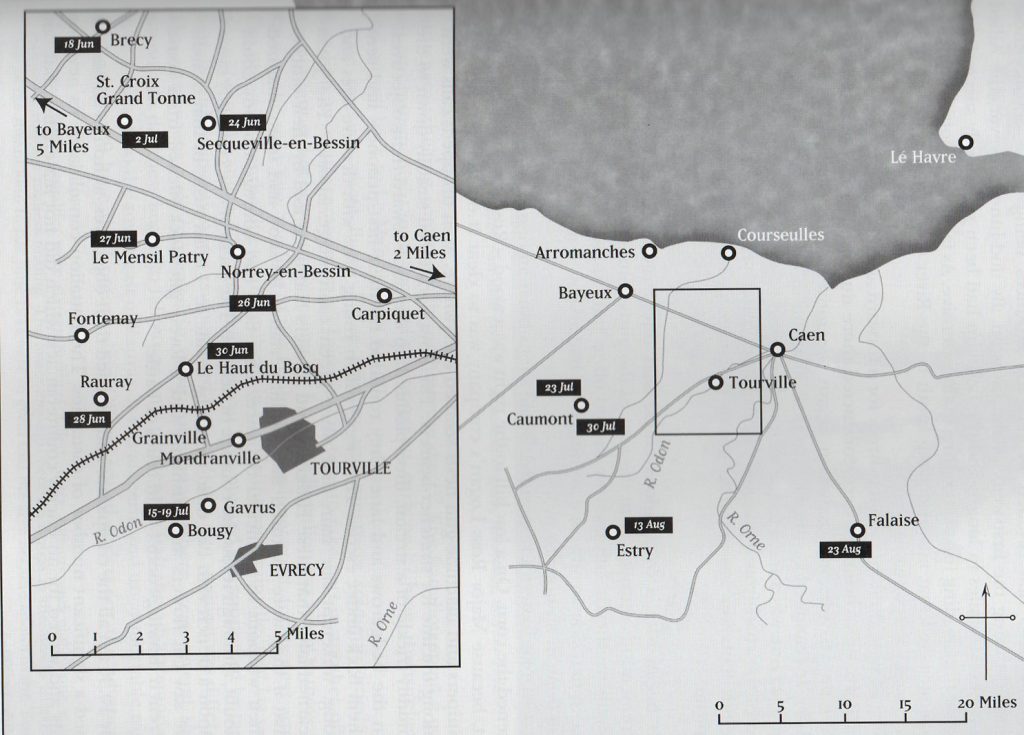

Normandy 18 June – 23 August 1944

The Battalion was involved in three major assaults in the close rolling country, criss-crossed with hedgerows, steep-sided lanes and small woods, during the operation which began for them on 26 June. The first attack quickly secured its objectives at the northern end of the Corridor, although at some cost from snipers, skilfully sited machine guns and, later, artillery and mortar fire. The Battalion was relieved early on the following morning and moved back to rest and be reinforced with 100 all ranks. That evening they set off again on their second attack, to expand the corridor to the east and secure a route to the River.

Moving forward past scout cars 28 June 1944

Advancing through a cornfield supported by tanks

After 36 hours of heavy fighting their objectives were secured and early on the morning of 30 June they were relieved and, after holding off German counter-attacks in an interim position, were withdrawn on 2 July to a rest area where they received a further 123 reinforcements. Amongst these was Major PR Layne-Joynt of the South Lancashire Regiment who took over as 2ic from Major Eykyn who had gone to command 11 RSF. By now a bridgehead had been secured over the River Odon and, on 7 July, they moved into this area before the break out to the south. On 16 July at 0530 the Battalion crossed its start line and, by 1015, had taken all their objectives including the villages of Gavrus and Bougy The fighting, however, was far from over. Throughout the remainder of the day it was subjected to air attacks, constant mortar fire and counter attacks. Its position was perilous as both flanks were exposed but, by late afternoon, it had driven back the enemy and consolidated its small bridgehead south of the Odon. Their attacks on Gavrus and Bougy were described as ‘classical examples of tank and infantry cooperation’. The Battalion had suffered 57 killed and 324 wounded or missing in just over three weeks of fighting in Normandy including the Commanding Officer Lieutenant Colonel Delacombe who was wounded by mortar fire at the start of the Battalion’s third attack, just after being awarded the DSO for his leadership in the earlier attacks. After recovering from his wounds he took command of 2 RS in Italy in January 1945 and then in Palestine where he had been awarded the MBE with the 1st Battalion in 1938. Major Layne-Joynt, although 42 years old, about 10 years more than most COs at that time, took over command of the 8th Battalion

After the breakout and German defeat at Falaise the Battalion took part in the rapid advance across France, crossing the Seine on 28th August and entering Belgium in early September.

Route of the 8th Battalion September 1944 – July 1945

The first serious resistance was encountered at Aart on the Meuse-Escaut Canal where the Battalion, having established a small bridgehead against light opposition on 14 September, were expanding it when the Germans put in a series of counter-attacks. Two were beaten off in the early afternoon but, as the day progressed, the opposition became more determined. At about 2200 a heavier attack than hitherto led by German tanks broke into the Royal Scots’ positions on the eastern side and along the bank of the canal. Ammunition was running short and it was clear that a dangerous crisis was developing. There was very heavy fighting and some great acts of bravery and outstanding leadership, notably in B Company, which had been cut off, withdrawing through the German lines in single file and complete silence – at one point moving alongside the Germans who must have mistaken them for German troops, into the Battalion bridgehead, now reduced to some 100 yards in width and 50 in depth, Losses continued to be heavy. Ammunition ran low but always at the last minute, or so it seemed, further supplies were ferried across the canal. Two jocks managed to bring an abandoned German anti-tank gun into action forcing some of the German armour to withdraw. The fighting died down at about 1100, 24 hours after the first German counter-attacks and, in the lull, 6 RSF got across the canal. This allowed the bridgehead to be slightly expanded but a further counter-attack forced the defenders back into the former very tight bridgehead. At about 2000 that evening 6 KOSB were further squeezed in.

It was planned that these two battalions would launch an attack at 0700 the following morning, Saturday 16 September. In the midst of the preparations, however, the Germans put in an attack of tremendous force. Throughout the morning German attacks continued; and even when there was a lull, the enemy gunners kept up their heavy and accurate concentrations. After dusk that evening it appeared that the Germans were massing for another assault. The Artillery Forward Observation Officer called for three minutes rapid fire from one hundred guns. Then silence, broken by some shouting which appeared to be calls for stretch bearers. Immediately another three minutes was unleashed followed by total silence for the rest of the night. The next morning, three days after the Battalion had established the bridgehead and of virtually continuous close range fighting, they filed down to the canal bank and returned to the other side. The last man to leave was the Commanding Officer who wanted to ensure that every Royal Scot had left the bridgehead. He was awarded the DSO for his leadership in this battle and the Regiment earned the Battle Honour Aart which is carried on the Queen’s Colour. The three days of fighting had cost the Battalion 163 casualties. After less than two days rest it was again in action, this time in the area of Eindhoven where it received 120 reinforcements but, by the end of the month, it had suffered a further 50 casualties.

In mid-November Colonel Layne-Joynt, having reached the age of 43, handed over command to Lieutenant Colonel Pearson A&SH. On 3 December the Battalion took part in the assault on Blerick the western suburb of Venlo It was notable for the fact that the Battalion was carried into the assault and right onto the objective in ‘Kangaroos’, Sherman tanks with the turret removed and able to carry a section of soldiers crouched inside, protected from enemy shellfire, who then dismounted over the top and set about the enemy.

A ‘Kangaroo’ with mounted infantry on board

Advancing on tanks south of Goch, February 1945

This was the first time the Regiment acted as armoured infantry. The end of 1944 and beginning of 1945 were relatively quiet but a period of exceptional tension and vigilance. By 23 January the Battalion was back in Tilburg to prepare for Operation Veritable the aim of which was to break into the Siegfried Line and destroy the enemy between the Maas and the Rhine. The attack began on 8 February with the Battalion’s main involvement around Goch on 18 and 19 February later described in the Brigade history as ‘perhaps the finest performance of The Royal Scots in the War’. Both the Commanding Officer and Major McQueen (CO 1RS 1957-59) were awarded the DSO for their actions there, the former the third CO in succession to be so decorated in just 7 months. An MC and two MMs were also won and some 300 prisoners taken It had been another month of heavy fighting with 26 killed and 115 wounded. At the end of the month the Division was withdrawn to prepare for its most ambitious and significant operation of the campaign – Operation Torchlight the crossing of the Rhine.

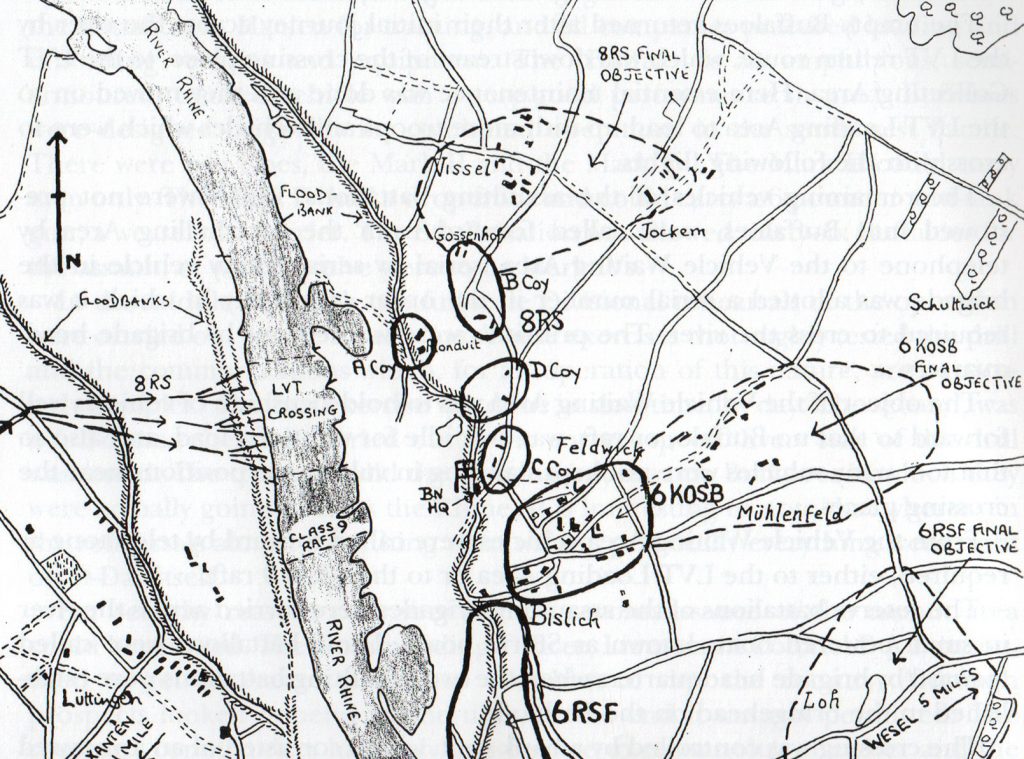

The Battalion moved back to Haelen in Holland where everyone was given 48 hours leave to Brussels, and morale soared! The Battalion went into hard and detailed training for their role as one of the lead assault battalions crossing the Rhine in Landing Vehicles Tracked (LVTs) or ‘Buffaloes’, well known to the 7th/9th Battalion from Walcheren but new to the 8th. It is not commonly known but the assault crossing of the Rhine was virtually an all-Scottish affair with 51st (Highland) Division in the North, 15th(Scottish) Division in the Centre and 4 Commando Brigade to the South. Every infantry Battalion in the assault force was Scottish and every Scottish infantry regiment was represented. In the middle of March two full-scale rehearsals of the operation were carried out on the River Maas. The first was done in slow time by day and the second was a full-dress rehearsal carried out at the correct speed by night. Every aspect of the crossing was tested with the troops doing the crossing in the actual Buffaloes in which they were going to cross the Rhine. It is interesting to note that, whereas in the rehearsals almost everything went wrong, practically everything went right on D-Day itself. The Battalion was allocated 36 Buffaloes to cross in four waves of nine.

8 RS. The Crossing of the Rhine 23-24 March 1945

44 Brigade was the right hand assault brigade of 15 Division wit 8 RS on the left and 6 RSF on the right with 6 KOSB in reserve to follow in assault boats. 8 RS left Haelen on 22 March reaching their marshalling area at around 0600 on the 23rd. The morning was spent resting before loading the Buffaloes that afternoon under cover of a vast smokescreen that had been covering the river and its approaches for some days. By a happy coincidence the near (west) bank from which the Battalion was to launch its assault was held by its sister Battalion, the 7th/9th. At 1800 a ferocious artillery barrage began across the river from every available gun At 2200 the Companies moved off to embark on their Buffaloes. Zero hour was at 0200 and punctually at that time the leading wave of Buffaloes, carrying A Company entered the water, followed at four minute intervals by three further waves carrying the rest of the assault element of the Battalion. About this time the enemy had come to life and some shelling and mortaring fell on the near bank and several Spandau machine guns opened up from the bund on the far side, but the firing was inaccurate and there were no casualties. A and B Companies quickly secured their objectives about half a mile inland from the far bank. But C Company had a hard fight, taking a number of casualties before securing theirs, At about 1000 the companies moved further to secure their second objectives about a mile inland. It was at this point that the massive airborne operation flew over at about 1000 feet to successfully drop, or land in gliders, the 6th Airborne Division about three miles further ahead. Radio communication was established with the airborne forces and by 1530 a patrol from the carrier platoon had made physical contact. There was to be no repeat of Arnhem. The Battalion had suffered 34 casualties in the day and had taken 310 prisoners.

The next morning the Battalion moved through the Airborne Division and after some stiff fighting by 0200 on the 26th had reached the autobahn running south to the Ruhr. That evening at 1900 the Battalion advanced again against a strong German position at Heisterhof which A Company eventually captured and held against a series of German counter-attacks. They were, however in a very precarious position with their left flank totally exposed as a result of 51st( (Highland) Division being held up in their advance. Every officer in A Company was wounded and, at one point, the Company ran out of ammunition but the attackers were held off by artillery fire until more ammunition arrived. The actions of Cpl Mallon of A Company deserve special mention. With both his platoon commander and sergeant wounded he took command of the platoon, drove off a German counter-attack through effective fire control and then, single handedly attacked a farmhouse in which some Germans had taken shelter. Despite being wounded in the side, and having lost his sten gun, he found two Germans hiding and physically attacked them, knocking one out whilst the other fled. He continued to command his platoon, in spite of his wound, until ordered back to the Regimental Aid Post. Not surprisingly he was awarded the Military Medal for his leadership and personal example. CSM Morton of C Company was also awarded the Military Medal for his actions that night. All the next day the Battalion defended the exposed left flank of the Brigade until late on the night of the 28th, five days after crossing the Rhine, the 15th (Scottish) Division were relieved by the 53rd (Welsh)Division. The Battalion had suffered a further 90 casualties. The Regiment was awarded the Battle Honour Rhine for their actions.

Follow-up elements disembarking from assault boats

8RS, supported by carriers, April 1945

The Battalion remained in the area of the Rhine until 4 April when it moved to the area of Borgholz near the Dortmund-Ems canal. Three days later it moved through Osnabruck en route to Minden on the Weser. From 10-20 April it moved every day until reaching Luneberg on the 20th, collecting many prisoners on the way. At Luneberg they spent a week ‘at rest’ in the old cavalry barracks there which allowed some sporting and social life – plus Battalion drill parades (with the Adjutant on a docile ex-German charger!). This ended abruptly on 29 April when the Battalion led yet another major assault river crossing, again in Buffaloes, this time of the Elbe. In many ways the crossing was harder and more unpleasant than that of the Rhine – there was not so much ground opposition, but very much more enemy shell and mortar fire, and even at this very late stage of the war, repeated enemy air attacks during the following morning on the crossing site. The Battalion suffered some 40 casualties in the crossing and a further six in the following days, including Major Drummond, who had commanded B Company since November, who sustained serious leg injuries from a shell on 2 May, Once established on the far bank nothing could hold them. During the next four days they pushed forward to Bargetheide, about 25 miles north of Hamburg, capturing many hundreds of prisoners en route. It was there, on 4 May, that they learnt of the total surrender of German forces on the Second Army Front.

It is wrong to single out one battalion of the Regiment in comparison with the deeds and actions of the others but the intensity of the 8th Battalion’s campaign in north-west Europe from 26 June 1944 – 4 May 1945 is reflected in the honours it gained and its casualty list. The honours included 4 DSOs. 7 MCs, and 12 MMs. 61 officers became casualties of whom13 were killed or died from their wounds and48 were wounded, captured or reported missing, Soldier casualties totalled 1,195: 224 killed or died of wounds and 971 wounded, captured or missing. These figures need to be seen against the war establishment of an infantry battalion: 37 officers and 845 soldiers. The overall percentage of casualties against the establishment was therefore 142 per cent, with 37 per cent killed. The ‘junior’ Battalion of the Regiment had earned its reputation in the traditional manner – a finely balanced mixture of highly professional competence and real determination.