THE QUINTINSHILL (GRETNA) TRAIN CRASH – 22 MAY 1915

At 6.49 am on Saturday 22 May 1915 a Liverpool-bound troop-train carrying half (498 all ranks) of the 7th (Leith) Battalion, The Royal Scots (The Royal Regiment) (7RS) collided head on with a local passenger train, which had been ‘parked’, facing north, on the south-bound main line at Quintinshill, just North of Gretna, to allow a following express to overtake it. Normally the local train would have been held in one of the loops at Quintinshill but both of these were already occupied by goods trains. The troop train overturned, mostly onto the neighbouring north-bound mainline track and, a minute later, the Glasgow-bound express ploughed into the wreckage causing it to burst into flame. The ferocity of the fire, and consequent difficulty of rescuing those trapped in the overturned and mangled carriages, was compounded by the fact that most of the carriages were very old, made of wood and lit by gas contained in a tank beneath them. Between the crash and the fire a total of 216 all ranks of 7RS and 12 others (see Note 1), mostly from the express but including the driver and fireman on the troop-train, died in, or as an immediate result of what was, and remains, Britain’s worst railway disaster.

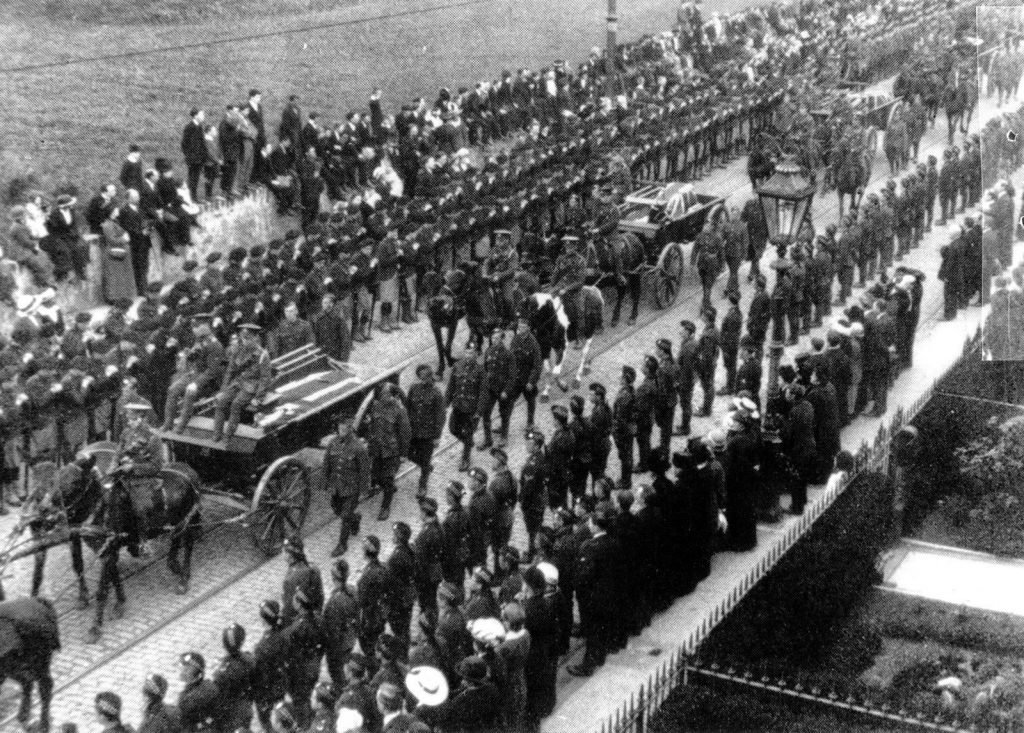

An artist’s impression of the crash as the Glasgow-bound express is about to hit the engine of the troop train

7RS, a Territorial battalion recruited mostly from Leith, then a separate Burgh from Edinburgh, had been mobilised at the start of The Great War and then employed on Coastal Defence duties on the Forth until April 1915 when they moved to Larbert, near Falkirk, to concentrate with 52nd Lowland Division before deploying to France. At the last moment orders were received changing the Division’s deployment to Gallipoli. The Battalion was meant to leave Larbert on 21 May to board the troopship Aquitania in Liverpool but she ran aground in the Mersey and the move was delayed twenty-four hours. At 3.45am on Saturday 22 May the first train left Larbert Station carrying Battalion Headquarters, A and D Companies. The accident happened at 6.49 a.m. The reaction to the accident was swift and spontaneous.

‘The survivors at once got to work to help their stricken comrades and soon the whole neighbourhood was alarmed, and motor cars from near and far hastened to the spot with medical and other help. The kindness shown on all hands will never be forgotten, especially by the people from the surrounding area and Carlisle who gave such valuable assistance to the injured. Their hospitals were soon overflowing, but all who needed attention were quickly made as comfortable as possible. Their Majesties The King and Queen early sent their sympathy and gifts to the hospitals.’

Of the half-battalion on the train only sixty-two survived unscathed. These survivors, including the Commanding Officer, continued on to Liverpool where six officers embarked, and sailed on the Sunday on HMT Empress of Britain with the second half of the Battalion, while one officer and the 55 NCO and soldier survivors were sent back to Edinburgh.

The Roll Call of the 62 survivors at Quintinshill being taken by the CO Lt Col Peebles

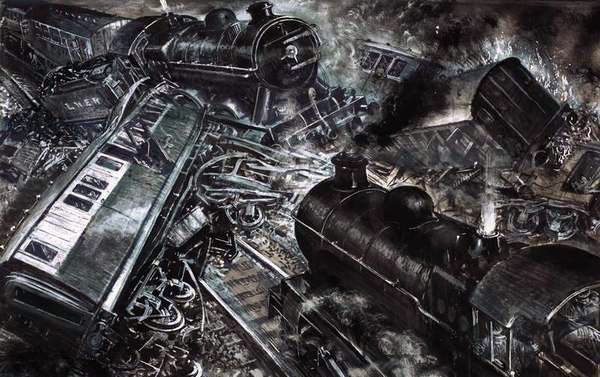

It was a devastating blow to the Battalion and to the whole population of Leith – it was said that there was not a family in the town untouched by the tragedy (see Note 2), probably made worse by the fact that, out of the 216 who died in the disaster, or soon afterwards from their injuries, only 83 were ever identified. The remaining 133 bodies could not be identified or were, literally, cremated within the firestorm of the wreckage. On Sunday 23rd 107 coffins were taken back to Edinburgh and were placed in the Battalion’s Drill Hall in Dalmeny Street, off Leith Walk. On the afternoon of Monday 24th May, 101 of these were taken in procession for burial in a mass grave that had been dug in Rosebank Cemetery, Pilrig Street, about a mile from the Drill Hall. ‘The route was lined by 3,150 soldiers [by comparison, the total figure on parade for Her Majesty’s Birthday Parade in London in 2013 was given as 1,000, including street liners], thousands of citizens stood shoulder to shoulder on the pavement; shops were closed, blinds drawn and the traffic stopped.’

The Funeral Procession to Rosebank Cemetery

A Board of Inquiry, convened three days after the crash, found a number of serious failings in procedure which, when combined, led to the disaster. The worst of these was the failure of the two signalmen on duty in the Quintinshill Box, now demolished, but which then immediately overlooked the crash site, to alert the troop-train to the local passenger train waiting in its path. Both signalmen were subsequently charged, appeared before the High Court in Edinburgh on 24 September, found guilty of culpable homicide and sentenced to periods of imprisonment, one of them with hard labour.

Very soon after the crash it was decided to raise a memorial, paid for by public subscription, alongside the communal grave in Rosebank Cemetery. The Memorial, unveiled by the Earl of Rosebery, Honorary Colonel of the Battalion, on 12 May 1916, takes the form of a Celtic cross, standing 15ft 6ins, made from Peterhead granite with an inscription and an explanatory plaque to the front and shields, bearing the Regimental Badge and Leith Burgh Coat-of-Arms, one on each side. On either side to the rear, against the Cemetery wall, are tablets each with five bronze plaques. On these plaques are the names of 214 who died in, or immediately after the disaster, arranged by rank, and in alphabetical order. These include the name of Sgt James Anderson, who died in September 1917 having never recovered from his injuries, and was added later. For some unknown reason the name of Pte George Garrie was missed out on the plaques although he appeared on all the lists, including those of the plaques, published later. His name, together with that of Pte William S Paterson, who was also missed out, is to be added on a separate plaque in 2015, bringing the final official total of 7RS killed in, or as a direct result of the crash, to 216. Although funded by public subscription, the Memorial has been adopted by The Commonwealth War Graves Commission who maintain it, and the grave area, superbly. Every year, on the Saturday closest to 22 May the Regimental Association, supported by local organisations, hold a Memorial Service and wreath laying at the Memorial. In 2015 major commemorations took place at Gretna on 22 May and at Rosebank Cemetery on the 23rd, both in the presence of HRH The Princess Royal, the Patron of The Association.

The memorial at Rosebank Cemetery

Notes.

1. The names of the dead are listed in this updated Roll. The 12 non-Royal Scots dead, in addition to the two crew of the troop-train, are, from the Glasgow-bound express, listed as two RN officers, three officers from 9th Battalion The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, two civilians and a sleeping car attendant, together with a mother and her baby son on the local train.

2. As a result of the Haldane Reforms of 1908 the Territorial Force (TF) was created from the old Volunteer and Yeomanry units. This led to five Royal Scots Territorial Battalions, the 4th,5th,6th, 7th and 9th(Highlanders) Battalions being based in and recruiting from different areas, and often different trades and similar groupings, across Edinburgh and Leith. The 7th Battalion, with their Drill Hall in Dalmeny Street, just within the then Burgh of Leith, drew nearly all its recruits from that Burgh, Portobello and, a sizeable number, concentrated in A Company, from neighbouring Musselburgh. This very local recruiting had not altered much by 1915 although the Battalion had been reinforced to War establishment for deployment overseas by a Company from 8th Battalion The Highland Light Infantry, drawn mostly from the Lanark area, two of whom were killed. Within the Battalion roll of those involved in the crash are listed a few men from the Lothians and from Fife and one, Pte John Fyfe, who was killed, from Lima, New York, USA.

For fuller details on the disaster see “The Quintinshill Conspiracy” by Jack Richards and Adrian Searle published by Pen and Sword Transport in 2013 (ISBN 978 1 78159 099 7), and “The Ill-Fated Battalion” by Peter Sain Ley Berry published by ECW Press in 2013 (ISBN 978 1 84914 414 8)